Insanity, Mastery, or Practice?

Doing the same thing over and over might only look like insanity.

Someone famously said that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. (It was not Albert Einstein.)

Chris Dreja, the original rhythm guitar player for the Yardbirds, said of Eric Clapton’s drive to master the blues early in his career: “He used to play a phrase for a week, the same four-note refrain.”

Malcolm Gladwell popularized the “10,000 hours to mastery rule,” which is not a rule but a theory about how deliberate practice and focused effort separate journeymen from master craftspeople.

[O]nce a musician has enough ability to get into a top music school, the thing that distinguishes one performer from another is how hard he or she works. That’s it.”1

I don’t want to talk about insanity or mastery. This is about practice. This is about understanding what is undesirable, what is changeable, what is inevitable, and when do we decide something is beyond our power? This is about action rather than aspirations. As Lucinda Williams sings, “If wishes were horses / I’d have a ranch / Come on and give me / another chance.”

It has become somewhat fashionable for us left-leaning types to call ourselves Progressives. Progressivism, like other isms, is a framework of ideas, beliefs, and methods in which we place our trust. But its efficacy comes through action.

The term “actionable” hit its peak use during the Progressive Era, which gained momentum starting in the post-Civil War dark days through Reconstruction, the Gilded Age, and reign of the Robber Barons, only to decline between WWI and WWII.

— Google Books Ngram

A dear friend and co-volunteer at Peace House Community died this summer following a long and mysterious malady that proved to be leukemia. She is the woman with the sunbeam on her face in the corner of the photo that accompanies my previous post, “When an Invisible Man Sees Himself.” At the conclusion of Not So Far from Home I acknowledge her as one of my inspirational creative role models.

She read these words but did not survive to hold the book in her hands:

Kathleen Zuckerman has mastered the arts of listening and learning, which she practices as the resident Peace House art lady and in-demand hand masseuse. She also serves on the advisory council that ensures the board hears community voices. She’s been a family caseworker, teacher in New York City and Chicago, and volunteered at a home for unwed mothers and a shelter for victims of domestic abuse. She’s guided by the question, “Where will I have the greatest impact on others—and on myself?”

My Wednesday co-volunteers Kathleen (r) and Mary Ellen at the tail end COVID-19 shutdowns.

Kathleen’s spiritual heritage was hard to pin down in a place that was founded by a Catholic nun. She made room for mystery as well as enlightenment. She grew up in a small Minnesota town settled by German immigrants that was also shaped by the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 and anti-German persecution and charges of sedition during WW-I. She was a convert to Judaism and a practicing Buddhist who embraced reverence for Mother Earth that was indistinguishable from that of our Native community members.

Kathleen exemplified the difference between single-minded repetition and a deliberate practice. She taught me—revealed to me—that practice is not a path to a specific outcome but an evolving state of being that grows through being fully present and aware; what some might call being intentional.

On the night before Kathleen’s memorial service at the Common Ground Meditation Center, I wanted to gather my thoughts about her. I sat in bed with a notebook and began to write whatever came forth. The first words were:

We all are going to die / you knew as I do / that was always part of the deal

As I considered the next line, a tiny fly of unknown species alighted on the tip of my pen. I paused. It stayed. I thought of reaching for my phone to snap a picture, but I wanted to let it perch undisturbed.

I thought of a conversation with Ellie two days before at Peace House. She told me of attending a funeral on the rez for one of her relatives. As they left the church, three eagles circled overhead and did not leave until the departed one’s body was brought out to the hearse.

The fly stayed as I wrote: / without having to read the fine print

Why didn’t it leave the moving pen? I stopped to contemplate. I don’t believe this stuff, but I considered Kathleen’s quietly profound way of communicating. Was she advising me not to take tomorrow too seriously?

Then the fly flew off and I tried to resume my task, but the moment was more powerful than anything I could write about it. And that was also Kathleen. Powerful in her stillness. In her unconditional love and acceptance. A human medicine bundle of all faiths, all causes, all places. Seeming to be always present, according to the many people who considered themselves to be her closest friend.

I shared the story of the fly at the service after Kathleen’s son told a funny and mystical story about a goat coming into a Dairy Queen. Kathleen, in hospice, was too weak to accompany the family to get an ice cream treat. When they arrived, sitting in the next car was a goat, an animal that had special significance to Kathleen. The goat and its owner followed them inside.

After the service, Tiegan, a woman who manages a nearby supportive housing facility came up to me. Just as I began my tale of the fly intervention, she told me she had a visitation from a tiny fly that settled on her hand.

I love those moments, I said, but really don’t believe in spirits like that. (I think people become more aware of the natural world during moments of heightened feeling and take comfort from the connection.)

“Well, I’m Native, and I do believe,” said Tiegan.

And this I do believe. Our differences are our power but they can obscure what we hold in common and why we belong together in this life.

A couple weeks ago I started to despair over the looming federal government shutdown, mass firings, and presidentially commanded National Guard troops sent as symbols of punishment rather than protection.

By some coincidence, I came across this post of mine written five years ago after a long day of concerted effort to uncertain effect.

Sleep Tight.

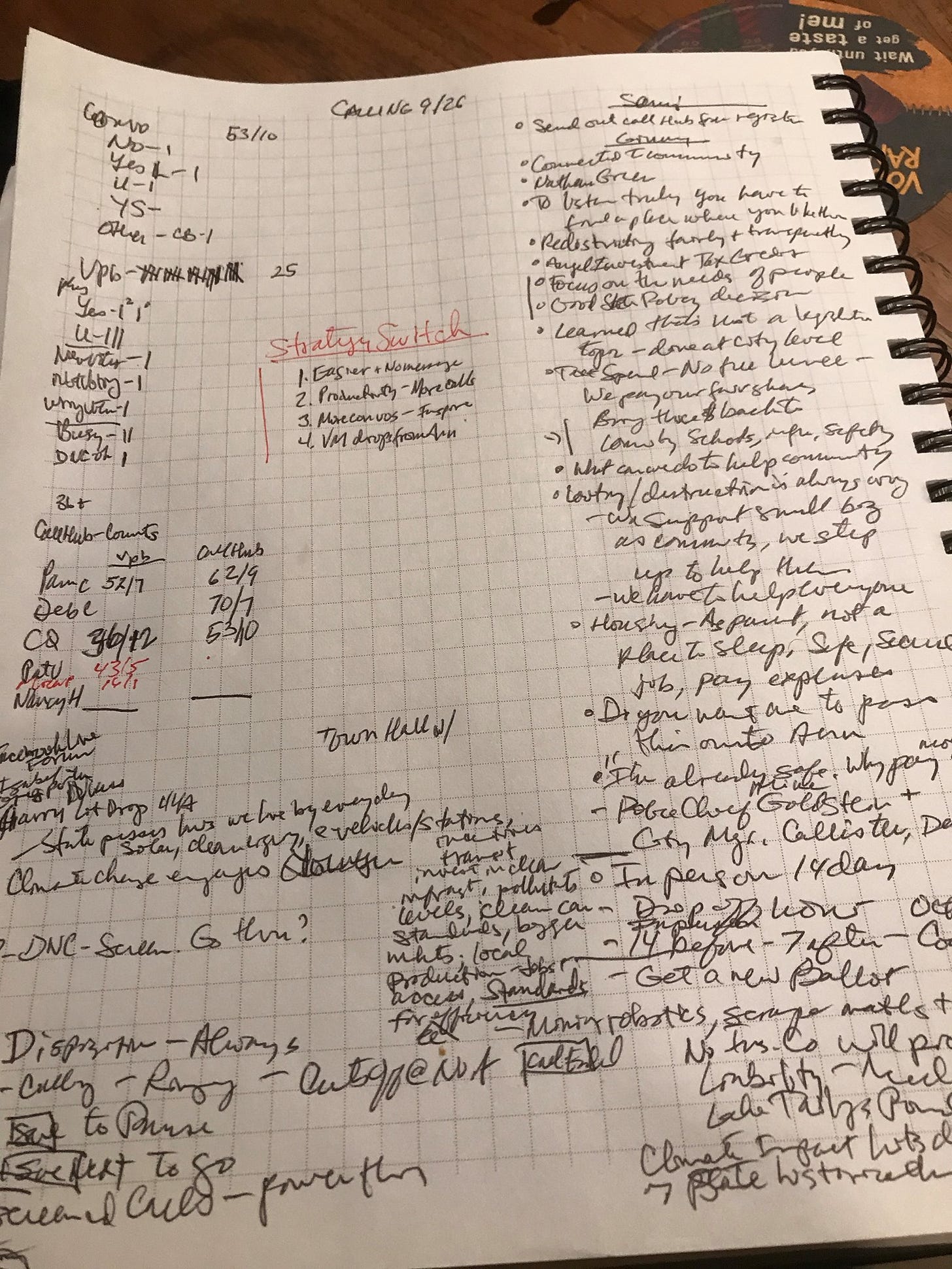

It’s 6:00 pm on Saturday. September 26, 2020. Since 9:30 this morning I have been working to change the course of our state legislature and to roll up my small efforts into a wave that diverts the nation from a terrible storm.

I felt worn and determined to read a book, but I’ve returned to my computer to share these thoughts so you could take them to bed tonight.

The day began with two women who will work together to represent their district if they win their races for state house and senate seats. This was not a public event or a secret session plotting America’s overthrow. It was a simple and aspirational conversation.

I wish you could have been there, regardless of your party or political beliefs. We talked about being connected to our communities, of how to truly listen to other people, of accepting our limited powers to influence national policy but also recognize that state and local governments have far more influence over how we live day to day.

We talked about not getting trapped into arguing or reinforcing negativity or unproductive exchanges. Instead, always returning to vision and values and the many opportunities to forge solutions once we shed fear, disinformation, and judgmentalism.

Though I know both candidates pretty well, there was much new today that made me respect them and know we are on the right path.

And without hearing one rah-rah statement, I turned enthusiastically to the task of calling strangers on the phone.

Midway through my calls I spoke to a woman with an Eastern European name who told me this would be the first election in which she could vote. She was excited yet measured and regarded her responsibility with gravity. She had not heard of my candidates, but she described the methodical, office-by-office process by which she would evaluate them.

I asked what would determine her votes, which issues were most important to her. She said she did not care about party or even specific issues so much as how a candidate represented her values.

And what were those?

Sometimes she paused to search for the precise word to express the nuances, but she left no doubt when stating her priorities. Someone who is positive and does not tear down the opposition or other groups. Someone who would include everyone in whatever policies they pursued. Someone who upheld what America has historically represented as an uplifting force in the world.

I congratulated her on her citizenship and thanked her for carrying out her responsibility with so much care.

The very next call, I spoke to a woman with two Chinese names followed by an English one. She also had not heard of my candidates, but she said it didn’t matter because she would not vote in November.

This seemed a curious choice by someone who had just registered to vote in January of this year. Reading the tone of her voice, I did not press for a reason or try to persuade her.

Perhaps I could have said, this is the most important election in our lifetime. But I do not know her life. Or how she views her future in this country.

To all my friends out there who are feeling despair or are sitting on the sidelines: don’t be paralyzed. That is the game being played; doubt and helplessness is political pandemic being unleashed against our democracy.

Our choice is not simply to be one of those voters or the other. We have to bring others along—the young, new, the dispossessed, the tired, the fearful. Connect their positive aspirations to ours.

So what are you going to do?

It’s 7:00 pm, and I am going to read my book.

Sleep tight.

Now it’s a new day in an ugly, unforeseen present. We can curl up in bed or in a book to calm our fears, but to master them we must gather ourselves internally and together. To take comfort in the fleeting moments. To accept that what will be will be, and to know that we can still practice the life we want to lead.

In his book Outliers, the researcher whose work Gladwell summaries clarifies that over-simplified quotation. Top music schools also tend to have top teachers. Good teaching, which includes feedback is an important variable that lifts talent and hard work to mastery.

I love this, Charlie, and will share with my sons who are very thoughtful.

Excellent piece. Thank you for taking the time to gather and share your reflections. Especially appreciated the final sentence. Good reminder for me.